Leading Questions: Sir Gary Verity

As Chief Executive of Welcome to Yorkshire, Sir Gary Verity played a crucial role in bringing the start of the Tour de France to the White Rose county for the first time

Chris Greany is Head of Group Investigations and Insider Threat at Barclays Chief Security Office, keeping the bank safe by identifying, investigating and preventing information and data leakage, and cyber criminality.

Chris joined Barclays after three decades in policing, including 20 years as a senior leader in counter-terrorism, security, intelligence and economic crime. He was part of the senior team that delivered the security strategy for British athletes, the royal family and VIPs at the 2012 Olympic Games and was the senior detective who led the investigation into the London riots of 2011. As Commander, he was the police advisor to government during many COBRA crisis committees, including the deployment of police specialists abroad in response to a number of international crises.

What was your early work experience?

When I was a young man, I had no clear ambition in life – like many young people I was kicking around, thinking a lot but not getting any answers. University wasn’t an option for a whole host of reasons. I went travelling around the world, and when you’ve travelled more and more, your horizons get wider but your ambitions and aspirations change.

I got back home having been free to travel and learn and thought: “I want a job that’s exciting and interesting”. I wanted to carry on the adventure I had experienced on my travels.

I wanted a career, but something that was exciting, and crucially made a difference to people. I’ve always tried to do the best for people, from the earliest days as a mountain climber taking underprivileged kids to the mountains to learn about themselves as people, and give them self-worth and confidence. I’ve always liked fixing problems – as humans we are full of them! – so, like many before me, I joined the police.

Then, and now, when you join the police you can start at the bottom and end up being at the top, and that’s how it worked for me. 31 years later I left the police and ended up working for a bank – something I thought I’d never do.

My joke with a friend in the early years of policing 20 years ago, when I was experiencing difficult leadership situations where true risk involved people’s lives, was: “It could be worse, we could be working for a bank”. Banking was very different back then – today it is a more dynamic and exciting place to work than ever.

How different is your leadership role at Barclays to those in your policing career?

When I joined, policing, like the military, was a disciplined service where what gets you through is camaraderie – you’re not massively well paid and the working conditions can be pretty rough. If you’re in counter-terrorism, as I was, then you’re going to see some gruesome stuff, often dealing with the finality of life.

What gets you through is training, camaraderie, leadership, being together, and a sense of joint mission. Your salary is not always based on how hard or long you work: everyone gets paid similarly and there’s a sort of simple beauty in that. There was an equality across roles, pay and gender. In some ways, you could argue that when it comes to equality, it was streets ahead.

So, when you come to a place like this, it’s different, but it’s also not all that different in terms of dealing with people and trying to get them to do the best they can, through whatever legitimate incentives you have to drive them. In policing, that driver was customer focus and camaraderie. Here it’s more monetised and that’s okay too. The reward is value and effort-based, and customer focus, whoever the customer is – internal or external – is key. That mind-set is crucial.

I’ve done talks about what I’m doing now and why I joined Barclays, and I always talk about what happened when I told my kids I was leaving the police and going to work in a bank. The police force was exciting to them – helicopters, boats, cars, dogs and horses – and they were sort of disappointed in me! Children should sit on the boards of global companies – they give brutally honest feedback! I told them: “Look, nothing has changed. I’m just a policeman in a bank”.

I joined Barclays because, having been on the other side looking in, I could see that here was a place driving legitimacy through value-based behaviour and I wanted to be part of that, having driven that culture for so long previously. Driving cultural change in any organisation is a marathon not a sprint – a bit like getting old in the mirror, it takes ages to see. It takes time, tenacity and bravery. Culture can be good and bad, it’s a way of doing things.

You need to harness the good and eradicate the bad, because if you don’t it will keep beating you. That’s where tenacity, bravery and experience come in. Whether its banking or policing, it’s the same.

Anyone in a leadership position who says they don’t have doubts is not being honest with themselves: doubts are your human checkpoint .

What key lessons have you learnt from other leaders during your career?

We all pick up beams of light from different people on our journey that help us create our own sun. There were several police and industry leaders who I aligned myself with because I loved their values – they had compassion and cared for people first, and they weren’t afraid to tell the truth.

“Speaking truth to power” is the toughest to do – and the hardest to receive. If as leader you are not getting honest feedback, you are setting the wrong culture and you will miss the big issues. Equally: build a diverse team around you. It’s uncomfortable sometimes, but then you get true feedback and that sort of feedback is a gift. Also, they lead by example, so they weren’t afraid to do something they asked you to do.

The other piece of feedback you learn about in senior positions, especially in the public sector, is people will say things about you that are not true. That can hurt, so you need broad shoulders – chin up and move forward. Don’t react to gossip and noise or you will amplify it, and don’t create it either. If you want everyone to like you then you will be disappointed, but they will respect you for being honest, making decisions, and not hiding from the tough issues.

These people and experience-based learning gave me the tools to lead. You can go through some dark times in your career and have doubts. Anyone in a leadership position who says they don’t have doubts is not being honest with themselves: doubts are your human checkpoint and that’s a critical leadership thing. The best thing to do with those doubts is to open up and ask people: “Am I getting this right, or am I way off?”.

Those people who are willing to accept feedback through difficult times will probably grow stronger. Those who don’t will disappear into a bubble of their own making and wonder why they’re not respected or why things went wrong.

How do you develop strong teams as a leader?

Leading by example is one part of it, but it’s not the only part. The idea of feedback is also important. Humans are terrified of telling people the truth – we want to gloss it over and put a nice sweetie wrapper on it because we’re afraid of saying to people: “You’re not up to it”. Honest feedback is key both ways.

You need to have channels for people to get advice and help. But those channels have got to be real, not paperwork channels. Some people who hit career trouble are those who just don’t know how to get traction, while some are people – whether they’ve been on leave for a long time or had something happen in their life that’s taken them off track – who can be brought back on and up. Most people you can get back on track by supporting, listening and developing.

As humans, if you expect someone to be on song for 40 years without a real break then you’re going to be disappointed. Everyone has their dips in life, and that will impact how you work as an individual.

As a leader, if you don’t recognise that, you’re condemning someone to failure. Emotional intelligence – and you can’t fake it – makes you more effective in terms of getting people to understand you as a leader. So, understanding what people’s lives are like and what makes them tick helps you as a leader understand how to get the best out of them. That’s authentic leadership. If you don’t know your staff, you’re missing a piece of the human jigsaw.

Take your work seriously, but don’t take yourself too seriously.

How do you unwind?

I ride horses and my kids ride. Horses will only respect you if you respect them, otherwise you get thrown or kicked off – you can’t trick them. You treat them well or get a hoof in the face: the respect has to be earned.

Having a good sense of humour also helps me unwind. An old friend in senior government who I worked closely with, told me there were three things to do to help you deal with all the things you see: first was not to take yourself too seriously, which I never have.

Second was not to get lost in the bubble of your own world, because it’s not reality to people out there. And third was to have some fun – all the tragedies you see are awful, but you’ve still got to function, somehow enjoy life, otherwise you become completely over-serious and fairly miserable. Take your work extremely seriously, but don’t take yourself too seriously.

How important is work/life balance?

It’s something that’s different for everyone. Some people are happy just to work, and do very few other things – they might be at a time in life where they can do that. Some people want to have a balance where they spend more time at home. Either way is legitimate as long as they continue to deliver, succeed and do whatever they need to for their organisation to be successful.

To me, the phrase “work/life balance” just means “make sure you are happy in your soul, because the evidence shows happy people work harder”. The police relied a lot on discretionary effort. There was a limited amount of money and people, so the only way we could get more was for people to go that extra mile and answer that call at midnight.

And the only way people will do that is if they’re being treated with respect and are generally happy. Then you basically have a larger workforce, through discretion. Good manners, respect and a sense of fair play are the foundation stone of this.

If you look at yourself in the mirror at night and think you’ve done the best you can, then that’s a good day.

What’s your perfect day at work?

I’m not someone who’ll say: “My day starts at 4am and I go to the gym and have granola”. Since as long as I can remember I’ve been nocturnal, and so early mornings aren’t my best time. I think that in the future, circadian rhythms will become a key part of how we hire people!

For me, it’s always been: come to work and enjoy it. Look at your workload. Mitigate your risks, and close them off at the end of the day if you can. A good day is going home and thinking “there’s nothing outstanding now” – that could be in policing where something hasn’t blown up, or in the bank where we haven’t lost any data. If you look at yourself in the mirror at night and think you’ve done the best you can, then that’s a good day.

What influence has your family had on your leadership ethic?

I think the experience of seeing the very worst humanity can offer makes you work your hardest to be a good, ethical and fair leader. My family grounds me and reminds me of the importance of doing your best, being kind and fair. These aren’t light touch leadership skills – the toughest leaders, the good ones, are kind and fair. They stand out.

As Chief Executive of Welcome to Yorkshire, Sir Gary Verity played a crucial role in bringing the start of the Tour de France to the White Rose county for the first time

Dambisa Moyo has been a Non-Executive Director on the board of Barclays since 2010

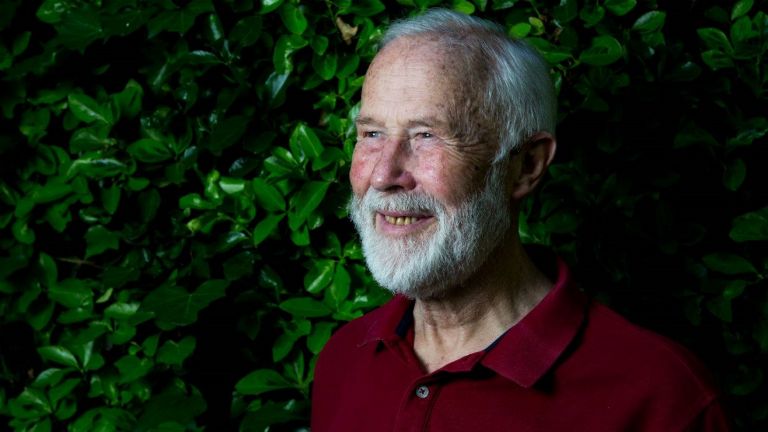

Sir Chris Bonington, 83, started climbing as a teenager in the 1950s and went on to become the UK's most celebrated mountaineer

Kathleen Britain joined Barclays in 2005 and was appointed Head of Charities for Barclays in 2016